The places that make it hard to work.

Poor workforce participation has deep roots in rocky soil. Here is how funders and workforce programs can get better results in states where it is an issue.

A quick note about this week’s special offer to honor my workforce hero.

Ten percent of all revenue I generate from JOBS THAT WORK supports The Cindi Beadle Memorial Fund, which honors my mom’s workforce journey by covering emergency costs that can derail the trajectory of nontraditional nursing students in North Alabama. To maximize the newsletter’s first quarterly donation, this week I’m running a special offer for paid subscriptions for groups and nonprofits providing training for good jobs:

Through March 30, I’m running a special 20% discount for annual group subscriptions of at least three, which you can take advantage of here or the button below. Basically, buy four ($400), get the fifth subscription free, and so on. I’ll also have a special discount for nonprofits providing training for good jobs, which I’ll explain below.

Of the amount I make from the sale up to $5,000, I’ll double my donation from 10% to 20%.

If I raise at least $5,001 off this week’s sale, I’ll donate half of the sale money to the fund.

If you’re a nonprofit training folks for good jobs, I have a special discount for you, but you have to email me by Friday.

Email me at nick@jobsthat.work with proof that (1) you’re a nonprofit and (2) you train people for good jobs with the subject line “NONPROFIT DISCOUNT REQUEST.” After verifying your information, I’ll send you a special offer by Friday. This offer provides a 30% discount on group subscriptions (e.g., pay $350 for five subscriptions or $700 for 10).

The issue

Low workforce participation irks business and political leaders in several Southern and Appalachian states. Workers aren’t the problem. It’s the place.

Wait, what?

In some places, it feels like the biggest challenge is getting people to work.

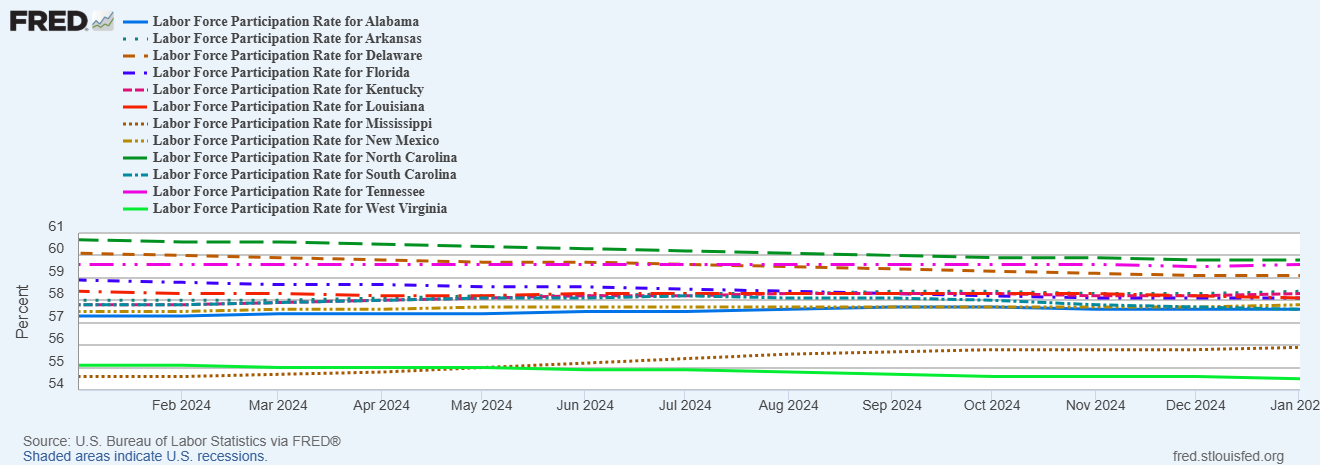

The workforce participation rate, for the uninitiated, measures who is looking for work and who holds a job. According to the Federal Reserve of St. Louis, nine of the 12 worst workforce participation rates in the country were in the Southeast or Appalachia in January 2025, the most recent month with available data.1 Mississippi and West Virginia’s rates are well below the rest of the country.

As you can imagine, political leaders in these states don’t love this. Corporate and business leaders also fret over low workforce participation because it could mean they have to pay more to get qualified talent2 and signal that fewer people are financially able to buy their companies’ goods and services.

I spent much of my last year at the Department of Labor thinking through this issue as I handled a portfolio of projects in the Southeast and Appalachia. After that work, I think of workforce participation as a good jobs problem split in two layers.

On one hand, you have the Employer Layer. This is the classic, Zeynep Ton, Costco-and-QT-offer-better-working-conditions-and-get-better-operational-results question of good jobs. There are great employers in the nine states above, but research says there also are plenty who don’t pay too well. In some of the states listed above, wages have not kept pace with inflation in highly publicized growth sectors, there has been perpetual wage stagnation, and some residents have seen wage decline.

But there also is a Place Layer to good jobs, where the place you live can make it harder or easier for you to enter the workforce, based on what tools your neighbors and leaders are willing to give you.

In some of the states above, political leaders have engaged3 this issue (at least somewhat) by discussing the benefits cliff, or when someone earns enough wages to lose public benefits, but not enough wages to live on without those services.4 This is a real problem and it’s hard to argue that it’s not a deterrent to work. If a job pays so low that it is functional unemployment, but the pay is still high enough that the state might take away your food benefits, why not go the route of actual unemployment with food?

But the benefits cliff is just a symptom of those deeper-seated issues that make work—and workforce development—harder in these states. In fairness to the political leaders of these states, I suspect discussing the benefits cliff is much easier than telling your colleagues they ought to give more tools to workers who aren’t working—especially if you enjoy being elected. Giving workers those tools means engaging the public services your voters are willing to fund, the costs of third- or fourth-generation efforts to thwart integration, and the prerogatives of your most well-moneyed and politically powerful stakeholders. Those latter stakeholders may include out-of-state companies that elected leaders lured using a friendlier regulatory environment and generous financial incentives that didn’t include hooks to ensure those incentives translated into good jobs for local workers.

I sympathize with those challenges as a professional who deals in politics. That said, having grown up in this region on death benefits with a parent who stretched her finances past the breaking point to get a good job, that sympathy has its limits. And they aren’t forgiving ones, if I’m being honest.

I often get questions about how to build workforce programs in this region. If you’re going to be successful getting these workers into jobs that need filling, you need to be clear-eyed as to what is keeping them out of the workforce—and the practical work you will need to do to overcome those problems.

Explain yourself.

Of the Appalachian and Southern states listed above:

Many have the highest concentration of people with disabilities while being among the worst places to live with disabilities.

Several have higher-than-average concentrations of people living in childcare deserts, places where there are no providers or too few providers to provide the care needed for children younger than 5.

Most are in the bottom 25 of states for accessing affordable healthcare.

And they are among the states that offer the least access to public or affordable transportation options.

And among the states with the worst public school systems in the country.

And among the states that have the overall highest concentrations of poverty in the country.

And almost all are among the worst states to work due to wage policies and limited worker protections.

So?

Well, for one:

For another, if the place around you makes it hard for you to get the education you need to get a job, or you don’t have a ride to your job and there is no dependable transportation for you because of your disability, or you don’t have anyone to take care of your kid while you’re at the job, or you can’t get the healthcare you need to be able to function at the job, or you don’t have a dependable way to enforce the labor rights that protect your job…

Well, it’s going to be hard to get a job and keep it.

What can we do about it?

I’m not going to ask you to fix how these states fundamentally work, although if you can do that, please go right ahead. (Appreciate it.)

More realistically, workforce programs—and the entities funding them—are more likely to succeed in these areas if they take steps like the ones below.

Plan supportive services early and structure grant competitions to require applicants to do the same.

In these states, it is essential to have full and thoughtful plans for supportive services, things like transportation and childcare and health services that help a worker get through a training program. For employers trying to attack this issue, I would recommend building employee benefit packages that do the same.5

It is very hard to do this work on the fly. I have seen grant applicants provide good on-paper plans for supportive services, then, once they have the money, not actually have the contacts or arrangements to get workers the services promised. Additionally, a la carte or as-needed approaches to these services cost more and risk losing participants who won’t be able to train without them. That is why I usually recommend providers have a firm plan, well before the project starts, for where and how they will provide each service their workers may need. I also recommend using cost-effective approaches like buying group subscriptions to online behavioral health services or the childcare strategy I describe below.

This isn’t just on training providers, though. If you’re funding a project based on a rough idea of the supportive services that an applicant might provide workers, you’re not investing your money smartly or efficiently. Granted, if you’re a funder who holds competitions, sometimes you’re not picking the best projects so much as the best-scoring applicants from a pool that neither God nor Devil nor 24-point bolded red serif text could get to grasp that applicants must have a clear and firm plan for supportive services.

But if I had my druthers (and of course I rarely do), I would make a thoughtful and complete supportive services plan a screen-out requirement in competitions—meaning that if you don’t have it in the application, your proposal doesn’t get evaluated.

Buy childcare slots on retainer.

It’s hard for people to get good jobs if they don’t have someone to safely care for the people they love the most. One option for workforce is what some white-shoe employers have done for years: pay a provider to make available a dependable number of childcare slots for your workers to use as needed.

When I talk about this idea, people often point out that the childcare needs of training programs can be short and unpredictable. The reason you pay a retainer is to have the services you need when you need them. And knowing their challenges, I don’t think childcare providers will turn you down if you help them improve their margins without creating significant new capacity needs.

Embrace the van.

I try not to point toward my own life for too many solutions to broader social needs—with one exception. I believe in the power of the noble van, of the type that the Tennessee Valley Authority sent out to ensure my father and other laborers in our part of the sticks made it from the Tennessee state line to Colbert Steam Plant. It may not work for all organizations or populations, but in terms of getting car-less workers around transit-less areas, it’s a lot easier than throwing a debit card at them and hoping they figure it out.

Plus, rechargeable electric vans appear cheaper in the long run.

Card subject to change.

Pending calamity, I won’t show up in your inbox again until Friday. These newsletters also should be morning-only occurrences going forwa—hey, I’m serious. Stop laughing.

FRIDAY: Grants listings plus a little speculation on the how of the Trump Administration’s approach to workforce and other grant awards.

NEXT TUESDAY: Looking ahead to the April 4 jobs report, which could mean a lot to the Trump Administration’s efforts to change the American workforce.

Three things:

First, I’m not addressing Florida in this pile because my rule is Florida Is Florida and Florida Breaks the Trend. We’ve glued so many disparate things together in that state that I don’t think it counts as “Southern” or “not a simulation” anymore, to be frank.

Second, New Mexico has had a noticeable dip in workforce participation over the past year. I would love to talk about this shift with someone knowledgeable about the state. Email nick@jobsthat.work.

Third, on Delaware, I’ll just drive north for a bit and shout until someone answers this question. I’ll update on my Del-Awareness as needed.

I highly recommend reading this pandemic-era story on worker shortages in Arkansas, which uses the phrase “drastic measures” to describe paying higher wages.

Separately, there is a vein of government leaders who try to downplay the number of people who aren’t working in their states. Unfortunately, these leaders appear to be in the states with the worst workforce participation rates in the country.

In this piece about West (By God) Virginia, leaders decide the real problem is that the workforce participation rate counts older people and people with disabilities. Therefore, they conclude, the measure is unfair and makes West Virginia look bad for no good reason. The story references that West Virginia has had the highest per capital rate of disability benefits claimants, and the leaders quoted in the piece appear to say they think it is impossible to get jobs for people with disabilities even if they “can walk.” First, yikes. Second, reasonable accommodation is still the law, kids!

Elsewhere, Gov. Tate Reeves maintains that Mississippi is such a cheap place to live that some people feel like they don’t have to work. “If an individual doesn’t want a job, the government ain’t going to force them to get a job,” Reeves said in November. “And that’s just a reality.”

Mississippi consistently has one of the worst rates of poverty in the country. Call me crazy, but that might have something to do with the cost of living.

First:

Second, if you want to understand the benefits cliff in more detail, read $2.00 a Day by Kathryn J. Edin and H. Luke Shaefer. The part about welfare reform will make you angry forever, but it’s essential reading for folks trying to do this work thoughtfully.

Also, they were staggered by the poverty in Mississippi and the little black- and gray-market economies that compensate for it.

While I focus on supportive services in the main text, many of these concepts can also apply to employee benefits.